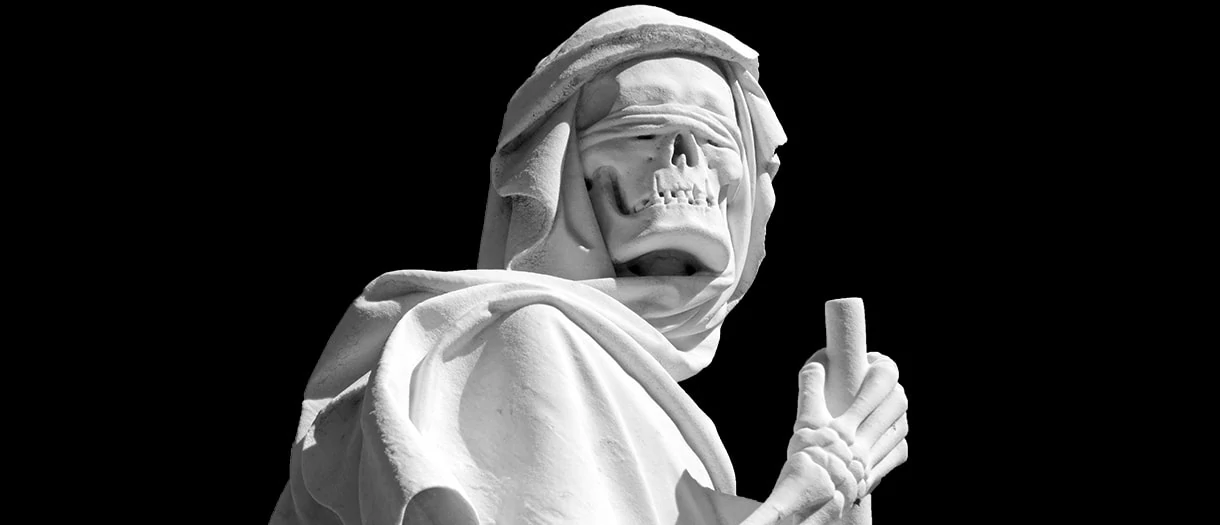

Time’s up, USP

The “unique selling proposition” has outlived its usefulness. Give it a gold watch and show it the door.

In his 1961 book Reality in Advertising, ad pioneer (and real-life Don Draper) Rosser Reeves coined a term that would long echo through corporate boardrooms and business-school classrooms: unique selling proposition (USP).

He coined the term to explain the success of the famously successful—and famously annoying—TV commercials he created for products like Anacin and Colgate.

According to Reeves, a USP has three requirements:

1. Each advertisement must make a proposition to the consumer. Each must say, “Buy this product, and you will get this specific benefit.” (For example, Anacin is “fast”; Colgate is “3 ways clean.”)

2. The proposition must be one that the competition either cannot, or does not, offer.

3. The proposition must be so strong that it can move the mass millions, i.e., pull over new customers to your product.

Compelling stuff for aspiring marketers, and certainly useful in its time—a time before channel surfing, massive product proliferation (in the early 1960s, there were five brands of toothpaste on the market; today there are 34, and hundreds of products within those brands) and the Internet. (Google “vintage Anacin ad”—if you can even last past the 30-second mark, you’ll see that this was advertising for a more patient world.)

The term has already outlasted Reeves by some 30 years, and it still shows signs of twitching life. Some marketers claim that in today’s ferociously competitive marketplace, the USP is more meaningful than ever—after all, how can a customer be convinced that your product or service is better than your competitors’ if you’re not telling them?

But there are several problems.

First, almost any apparent product advantage—from fast-acting relief to free ringtones—can be copied almost overnight. This is hardly a new concern. Listen to Al Ries and Jack Trout in their classic 1981 book, Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind: “In the late fifties, technology started to rear its ugly head. It became more and more difficult to establish that ‘USP’… Your ‘better mousetrap’ was followed by two more just like it. Both claiming to be better than the first one.”

Next, few customers are waiting to be told by advertisers why such-and-such advantage makes such-and-such product a better choice than its competitors. We can find out in seconds—through online reviews, price comparisons, blog roundups—what product suits our particular needs best. (Thanks, Google!)

If, that is, we are even putting that much thought into it. What makes us pluck Coca-Cola or Dad’s root beer or Jones Soda out of a sea of soft-drink brands? Visibility. Habit. A semi-subconscious desire to link our story with that of the brand. But not any trumped-up, fizzier-than-thou claim about the beverage’s superiority. (Remember point #2 in Rosser’s definition? “Buy this product, and you will get this specific benefit.”)

In fact, a USP for USP’s sake can even hurt sales. Or at least draw a few snickers. Copywriter Brian Thompson notably poked fun at beer companies’ clumsy attempts at uniqueness, from Budweiser’s Flavor-Lock Crown (“The best thing you can say is that your beer has a bottle cap. Really?”) to Coors Light’s wide-mouth can (to which Heineken cheekily replied in an ad for its own redesigned can, “The mouth’s not any wider. But gravity still exists, right?”).

This isn’t to say that you might as well toss in the towel and melt into a hazy landscape of indistinguishable brands. But to rely on the USP for distinction is about as effective as sending your correspondence by telegraph. Like many great inventions, it’s simply run its course. It started big, made an impact, but now appears as a quaint relic of a simpler time, having been overtaken by decades of an increasingly more sophisticated (though still incomplete) understanding of the rational and irrational bases of the choices we make as consumers.

The USP has worked long and hard, but it’s well past retirement age. So let’s hand over its gold watch and send it on its way.

Because there are some promising applicants looking to fill its position. Heck, they already have.