Flying colours

Advice on how to make colour choices less subjective—and more visually powerful—in your brand arsenal.

When Pantone announced rose and quartz as their “Color* of the Year” for 2016, the heated commentary that followed (apart from the fact that they named two selections!) gives us a sense of the power of colour. “Yuck,” “ugh” and “ick” seemed to be the social media consensus for the duo that was supposed to carry more weighty purposes: first, according to Pantone, they help us find a yearned-after sense of security in troubled times, and second, they help reflect the blurring of lines between gender roles.

So what is it about colour that makes people react so viscerally and with such hyperbole?

After all, as Jude Stewart, who has written extensively on the topic, states, “in addition to all its culturally saturated meanings”—more on this point later—“the color spectrum is also just a series of intervals, a visually spliced way of expressing gradations.”

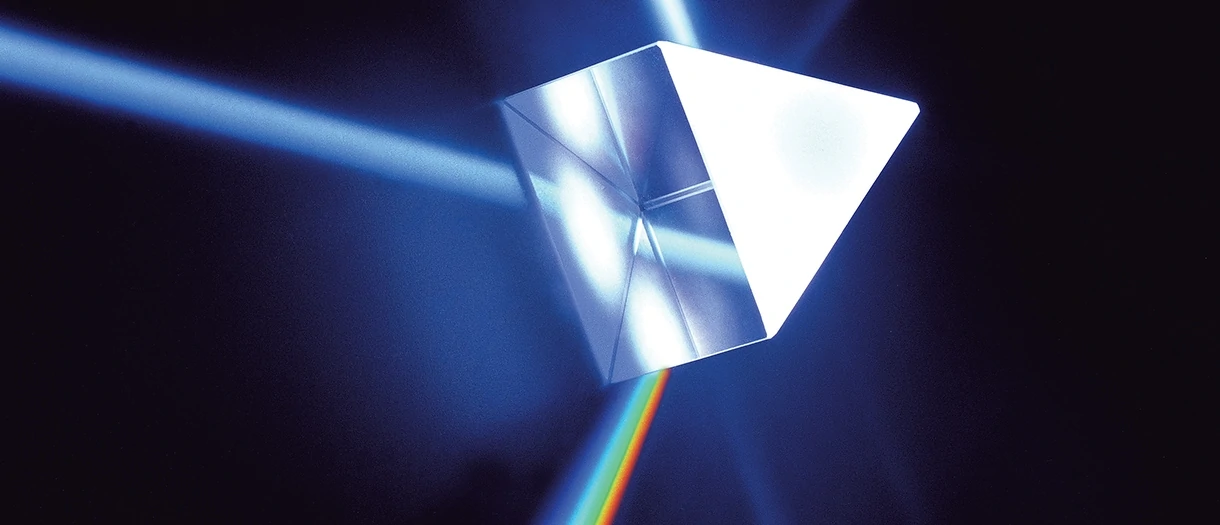

In other words, when you boil it down, colour is just a reflection of light off a surface, or light radiating from a source. After that, we need to look at culture and context to understand why there are so many strong reactions to colours and their meanings.

For example, red is the colour of hot coals, but do hot coals signify the comfort of warmth or the pain of a burn? Red gets even more complicated in terms of context: it gives us associations of ripe strawberries, apples and cherries—as well as blood.

It’s been my experience via 25 years in design that colour’s “culturally saturated meanings”—especially with brand identity projects—can derail the most well-thought-out choices. It’s perhaps the most subjective element of any branding assignment.

While there’s no formula to choosing the perfect hue, I’m happy to share some insights that can help get you there.

Do you need to stand out or fit in?

First, you need to look at your marketplace and its use of colour. In some categories, you need to review your competitors and choose a colour that differentiates against them. For example, Canadian banks have carved up most of the common corporate colours (blue and yellow for RBC, red for Scotiabank, green for TD Canada Trust, etc.). New players (like Tangerine) simply pick a different spot on the spectrum.

In other cases, your brand’s colour may need to fit in—more commonly seen in many consumer packaged goods. One example is milk packaging: red is almost exclusively used for whole milk, various shades of blue for 2% and light blue to green for skim. Potato chips are another example; in this case, the bag typically reflects the flavours within: red for ketchup, orange or deep red for barbecue, green for jalapeno, etc.

In these examples, the colour system provides a shortcut to the busy shopper, who can quickly and easily select the product they want. Some brands try to disrupt that system, but they do so at the risk of making it that much harder for the customer to choose their product—almost never a good idea.

The (flawed) science of colour

You may remember the famous Hubspot colour test. They tested a “call to action” button on their website via two cloned pages, with the only difference being a green “get started now” on some pages and a red one on others. The red button outperformed the green button by 21% more clicks.

So, it’s safe to conclude that all buttons on the web should be red, right?

Well, maybe not. It’s impossible to rule out the design of the page and how that affected the outcome. In Hubspot’s experiment, the page design had many other green elements (such as the Hubspot logo). Against that, the red button provided a clear contrast. If the page had featured many elements in red, would we have seen a different outcome? Add to that the fact that the pages only had 2,000 visits during the test, and the results never state the actual number of clickthroughs (“21% more” could be a statistically meaningless number). To Hubspot’s credit, they’re clear about the limitations of the test, warning readers, “do not go out and blindly switch your green buttons to red without testing first”—but a lot of people missed this caveat.

Science has shown us how colour can affect how we feel or make decisions—the colour of a wall in a schoolroom, prison or office can affect how we work and interact. But it’s hard to prove that colour by itself can make us change our decision making or even our habits.

In some categories, you need to review your competitors, and choose a colour that differentiates against them. In other cases, your brand’s colour may need to fit in—more commonly seen in many consumer packaged goods.

Still, we can count on a few facts about colour

According to a study on colorcom.com, visual appearance influences 93% of purchasing decisions, with 85% of consumers citing colour as the primary reason why they buy a product. In addition, a 2002 study called “The Contributions of Color to Recognition Memory for Natural Scenes,” led by Felix A. Wichmann, found that colour helps us to process and remember images better than colourless (black and white) scenes.

Firing up the brain cells

Even scientifically, colour sometimes works in contradictory ways. Jay Neitz, a colour vision scientist at the University of Washington, states that “the reason we feel happy when we see red, orange and yellow light is because we’re stimulating this ancient blue-yellow visual system. But our conscious perception of blue and yellow comes from a completely different circuitry—the cone cells. So the fact that we have similar emotional reactions to different lights doesn’t mean our perceptions of the color of the light are the same.”

In other words, what you see as blue might be different from what I see, but, according to Neitz, that doesn’t really matter—it’s the emotional reaction to that particular light that matters. People with damage to the parts of the brain that help us perceive colour may not be able to perceive the same hues as other people, but they would likely have the same emotional reaction to the light as anyone else.

Be aware of cultural considerations—but don’t take them too seriously

We’ve all been told that Westerners tend to associate yellow with sunshine and optimism, and red with danger or passion—and in China, white is most associated with mourning.

In the West, black often communicates death, but also luxury and sophistication (James Bond never wore a purple tuxedo; only Austin Powers would). How can one colour symbolize such opposing meanings?

In my experience, context beats culture every time; in fact, context is generally at the root of most visual symbolism.

Wearing black only represents mourning if you understand that the wearer has been or will be attending a funeral.

Keep it simple

Quick: What colours are in the Olympics logo? What colour is FedEx Ground, FedEx Office, FedEx Freight or FedEx Trade Networks?

Most people can only remember one colour, maybe two of a well-known brand—the general rule is to pick a colour and own it in your market.

Multi-colour systems tend not to work—that is, a brand in which division one is blue, division two is red, etc. Only the people who work with the brand every day can remember this kind of complexity.

Finally, choose colours that can be reproduced consistently

In my experience, the biggest issue isn’t what colour ultimately gets picked. The biggest issue is ensuring your colour palette doesn’t contain any properties that are hard to reproduce consistently.

For example, certain colours—orange, in particular—are notoriously different when printed via a four-colour process or are difficult to match from one colour system or device to another.

Part art, part science

Despite all of colour’s subjectivity, it’s still one of the most powerful tools in a brand’s arsenal. When you see a turquoise box handed to someone, you don’t need to see the logo to know it’s from Tiffany’s and that a range of emotions will have been stirred. Most fire trucks are still red (despite knowing that bright yellow would help drivers and pedestrians see the rushing vehicles more quickly, day or night). House-brand drugs always copy the brand leader’s colours—but would a blue acetaminophen package make the drug less effective?

Choosing colours is not a science, nor is it an art—it’s somewhere in between. As a brand owner, manager or steward, remember this: it’s not important that you like your brand’s colour—you just need to make sure that it’s doing what it needs to do.

*Yes, we know colour is spelled with a “u” in Canada and most respectable places. Pedantic editors that we are, however, we try to keep the spelling of the country of origin for quotes, titles, etc., so do us a favour and just go with it.

Some basic rules

Here are a few points to remember when choosing colours for your brand identity:

- Your likes and dislikes have nothing to do with picking brand colours.

- Voting, or committees, can’t pick the right colour for your brand.

- Choose a colour that makes sense for your category—for example, green is good for farm equipment (but John Deere got there first); brown never feels high-tech.

- Make sure your colour is different from your competitors’ if you need to differentiate.

- If colour can help the customer find you easily, follow the colour that is based on a category’s code.

- Once you choose a colour, own it—beware of agencies that want to expand or wander from it.