Sequels, spinoffs and slip-ups

Brand extensions—a help or a hindrance?

As consumers, we’re susceptible to and comforted by the familiar, and marketers know it. A brand will capitalize on its success by creating another product with the hope that its specific, recognizable magic will transfer seamlessly to the new product, expanding reach in the marketplace. Brand extension is sometimes considered a savvy, budget-conscious, low-risk way to take something that cooks in one arena and make it sing in another.

Unless it doesn’t.

“Logic is on the side of the line extension,” wrote Al Ries and Jack Trout in their marketing bible Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind, before offering a passel of reasons why logic doesn’t matter in this business practice.

The book makes the case that brand extensions are a trap: they dilute a brand, confuse the consumer, and shouldn’t be attempted by rational, forward-thinking brand caretakers. Ries and Trout offer colourful, historical examples of expensive market duds—when Life Savers candy attempted to get into gum, and when Mazola, a big name in corn oil, jumped into the margarine business.

And yet here we are in 2018—surrounded by extension success stories, sequels and spinoffs.

Key to those successes is having a good sense of the brand’s consumer perception in the marketplace, and knowing how to best add value to that perception. But even then, brand extension is rarely a slam dunk, and sometimes a win owes a lot to plain old luck.

This year is the 50th anniversary of the Big Mac, McDonald’s flagship burger and the most recognizable product of the most successful restaurant chain in the world. And yet it’s estimated that only one in five millennials has ever even tried a Big Mac, according to a 2016 memo written by a top McDonald’s franchisee.

Perhaps to bridge this generation gap, the fast-food giant recently test-drove a Sriracha Big Mac at McDonald’s locations in San Diego, Los Angeles, Seattle and Ohio. These burgers also included kale and spinach instead of traditional iceberg lettuce.

Maybe sensing that the spicy burger’s appeal wasn’t enough of an experiment for the birthday year, McDonald’s also introduced another limited-time treat in some locations: the Mac Jr. and Grand Mac, smaller and larger Big Mac variations, respectively.

It remains to be seen whether any of the McDonald’s burger alternatives will catch on and become a more permanent part of the menu, but their appearance, along with the popular stand-alone McCafé locations, shows the burger giant isn’t afraid of messing with its formula and extending the brand to attract new customers (even after some famous fails—see below).

The future of extensions may be in unusual partnerships, where the shared risk helps shield participating brands from an extension failure. Hollywood has been paying attention. To use just one studio as an example, Warner Bros. has seen successful film partnerships with the Harry Potter series of books, Lego toys and DC comics. Over in Sweden, automaker Volvo and boutique hotel Tablet have coupled up to offer a “branded experience”: a pop-up lodge getaway that includes a brand-new car to enjoy in a wintry wonderland.

Speaking of Sweden, it was reported that IKEA is working with London officials to launch an affordable-living neighbourhood of more than 1,000 homes and apartments in the East End. That said, the ubiquitous Scandinavian furniture-maker has driven this project under a different name, Vastint, its real estate division, putting a little distance between the new venture and the parent company. Even IKEA might not be immune to an extension too far.

Brand Extension Hits

Ferrari World

Ferrari has been a manufacturer of high-performance Italian sports cars since 1939, with a brand that’s associated internationally with luxury, exclusivity and speed. A theme park may seem to be the least exclusive kind of brand extension, but Ferrari has one. Ferrari World Abu Dhabi, the largest indoor theme park on Earth, opened in the United Arab Emirates in 2010 and has become a popular, award-winning tourist attraction. It offers customers the opportunity to eat food prepared by celebrated Italian chefs, drive one of the company’s legendary automobiles and ride a rollercoaster called the Formula Rossa. Its claim to fame? The world’s fastest, of course. And if the idea of a theme park still feels gauche, somehow diminishing Ferrari’s high-end brand, the price of a ticket is still quite exclusive at 525 UAE dirham, or approximately $178 CAD, for a one-day “gold” pass.

Alan Cumming merch

It’s not a new idea for celebrities to parlay their unique appeal into new business arenas, but this is maybe the most playful and unexpected. Scottish film, TV and theatre actor Alan Cumming sells body products with his name on them. He’s said he was teased about his name for years and has recognized it’s ripe for wordplay. Gawker called his product names “impenetrably coy,” including a fragrance entitled 2nd Cumming. It’s not something every Hollywood star could get away with, but Cumming—whom the New York Times once described as a “bawdy, countercultural sprite”—has a niche presence as a public figure. Leveraging his name in a naughty way makes a clever play, but time will tell if consumers tire of the double entendre.

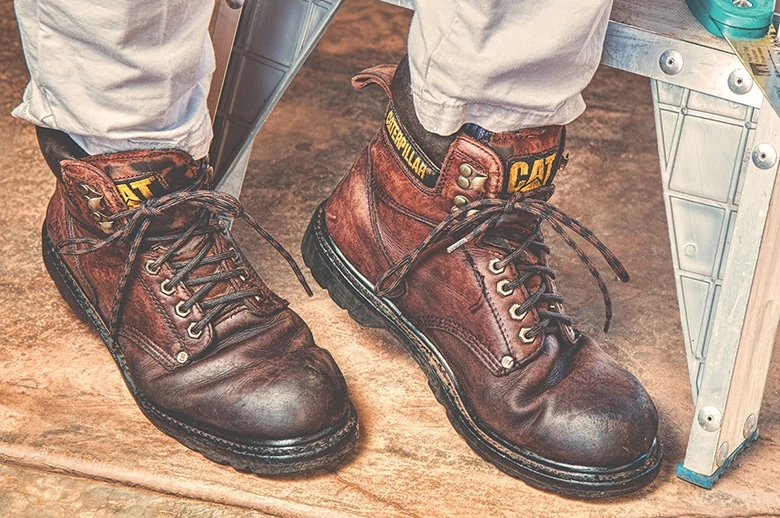

Caterpillar boots and cell phones

The Illinois-based heavy-equipment manufacturer has been making tractors and other earthmoving machines since 1925, earning a reputation for ruggedness and reliability. The strength of that reputation—and the recognizable Caterpillar yellow and black logo—has been featured in a popular line of shoes and work boots licensed by Wolverine, the footwear maker. More recently, Cat smartphones have entered the market from British licensee Bullitt: heavy-duty, hard-to-break mobiles with thermal imaging technology, which can be useful to people working in everything from construction to emergency services. Both these products cleverly leverage a brand synonymous with toughness and blue-collar utility.

Brand Extension Misses

McDonald’s Pizza

Not all of McDonald’s brand extensions have gone as well as the Egg McMuffin, the Chicken McNugget or McCafé. Pizza was introduced in the late 1980s, with a reported 40% of McDonald’s outlets in the United States including pizza on the menu, but it didn’t last. The official line is that the 11 minutes the pizza took to prepare was too long for the fast-food chain’s famously speedy service times, but it’s also been suggested that McDonald’s customers were slow to accept the burger joint as a pizzeria (and if memory serves, the pizza wasn’t very good).

Various Virgin stuff

Richard Branson is one of the world’s most fearless and famous entrepreneurs, his Virgin brand expanding with much success from a record label to record stores to airlines to wine. However, not all his concepts have worked, including the short-lived Virgin Cola, Virgin Cars and Virgin Brides, a chain of boutiques across the UK offering wedding dresses—Branson wore one for the store’s launch. But his ability to pick up, dust off and try something new despite frequent failure has endeared Branson to the public, making the Virgin brand remarkably resilient.

Harley-Davidson fragrances

As Matt Haig explained in his book, Brand Failures: The Truth about the 100 Biggest Branding Mistakes of All Time, Harley-Davidson’s customers consider the motorcycle maker an American legend, inseparable from their cherished values of freedom and masculinity. When the company attached its name to aftershave and perfume, with names like “Hot Road” and “Destiny,” Haig wrote that for Harley believers, “this was an extension too far.” Harley learned its lesson and eventually backpedalled, and has since been more selective choosing products on which to affix its logo.