Woke? Or joke?

Summary

Businesses of all sizes, from corner cafés to Anheuser-Busch, have become much more vocal about their values. But for every successful Nike “if you let me play” campaign, there are a dozen cautionary tales

from big brands cratering their public image with disingenuous messaging. Still, it makes plenty of sense for brands to ally themselves with causes close to their hearts—especially for new businesses that have yet to define their brand. This article offers guidance on how to do it right: start small, work with an organization you believe in, and let your values become a natural part of your brand’s DNA.

Customers increasingly expect brands to stand up for causes—just make sure you don’t overstate your case.

Customers increasingly expect brands to stand up for causes—just make sure you don’t overstate your case.

Drink a Pepsi, join a protest. Buy a pair of Nikes, stand up against racism. Pop open a bottle of Budweiser, stick it to the president of the United States. Ten years ago, none of those connections would have made a lot of sense—and you certainly wouldn’t have seen them as the central messages in massive ad campaigns.

Some brands have always stood for a specific cause—for example, The Body Shop’s raison d’etre was to provide and promote an alternative to animal testing of cosmetics, and Benetton for years ran a successful (wildly successful, from a PR standpoint) campaign that steadfastly pushed the limits of social issues—but these were historically in the minority.

Fearful of alienating any potential customer, most big brands remained “cause-agnostic”; on the rare occasions when they did take a stand, they generally aligned themselves with broadly palatable, middle-of-the-road causes such as national pride during the Olympics, commitment to good jobs, honouring historical achievements and the like.

Expect to polarize the public

But these days, brands that have been traditionally more neutral in their messaging are increasingly making polarizing political stances a central part of their identities.

Take Budweiser. Known for goofy, catchphrase-spewing ads (e.g., the wildly popular “Whassup?” series), the American beer giant’s 2017 Super Bowl ad paid homage to its founder’s roots as a poor immigrant from Germany, just as the Trump administration painted refugees and immigrants as the cause of any number of (fictional) problems.

All too predictably, offended viewers took to social media to call for a boycott of Bud products, thereby keeping Budweiser’s name in the news for days longer than a less controversial ad would have. Others rushed to praise Anheuser-Busch InBev, the world’s largest brewing company, for becoming “woke.”1 Skeptics saw the ad as a cynical ploy to get good press without having necessarily done anything to deserve it.

No matter how you slice it, though, it generated the kind of publicity that any company would dream of getting. (The company moved on to relatively safer topics in the following two years—community service and renewable energy.)

Nike has staked out an even-more controversial position on social issues, from signing a partnership in 2018 with Colin Kaepernick, the NFL quarterback who protested racial injustice by kneeling during the American national anthem, to running an ad campaign featuring narration from Serena Williams that asked pointed questions about why female athletes earn less money than their male counterparts.

The Kaepernick news led, unsurprisingly, to calls for a boycott of Nike, this time featuring people burning their Nikes in videos circulated on Twitter. Nike execs probably couldn’t have been happier—getting denounced by this particular cohort of Americans (who ended up, rightly or wrongly, being lumped in with Trumpites for sharing the president’s outraged reaction to the ads) was guaranteed to build currency with youth and social media-savvy athletes: a branding coup.

What does “woke” mean, you might be asking? Without going into an inscrutable, paragraphs-long explanation of online culture in the 2010s, it’s a term popularized by Black Lives Matter and related activist groups that refers to someone who has “awoken” to the assorted and interlocking structural injustices—racism, sexism, homophobia, etc.—that stubbornly persist in society.

Superficial can be worse than nothing at all

But attempting to be woke can go wrong, too. Few ads have been met with as much derision this decade as Pepsi’s “protest” ad from 2017, in which Kendall Jenner, fresh from a photo shoot, manages to calm tensions between young people protesting … something (it’s never made clear) and police officers by handing them cans of Pepsi (that the protesters apparently had chilling nearby in a large, telegenic cooler).

While none of it made much sense, Pepsi, at least, quickly realized how bad the ad was and pulled it, leaving it to live on in our memories (and on YouTube, where at least 13 million people have watched the ad since).

Or a more recent example: ancestry.com, in advertising their DNA testing services, dramatized the alleged love story of a white man and an enslaved black woman in the antebellum Southern US. The man proposes to his lover, and then asks if she would abscond with him to freedom in the North to be wed.

Commentators on Twitter were having absolutely none of it, pointing out that there were vastly more likely—and nonconsensual—means by which someone in 2019 would have had mixed ancestors in the era of slavery.

Ignoring this history of trauma and violence to sell DNA tests is the definition of poor taste. Ancestry.com at least had the sense to pull the ad, but also gave a weak apology that didn’t take any responsibility for the short-sighted campaign: “[we] apologize for any offense that the ad may have caused” is textbook buck-passing.

And once more, we have Budweiser. In April 2019, Budweiser received considerable plaudits for an ad they commissioned to mark the retirement of Dwyane Wade, a leading NBA player. In the ad, Wade stands in the middle of a darkened basketball court as five people whose lives he affected come to speak with him, including a woman whose younger brother, who idolized Wade, was killed in the Stoneman Douglas school shooting; a young Latina woman who had her university paid for by Wade’s scholarship foundation; and Wade’s own mother, who credited Wade’s unwavering support for her overcoming her battles with alcohol.

Budweiser wisely stepped away from the spotlight and let Wade’s legacy of humanitarian work and upstanding citizenship take centre stage, resulting

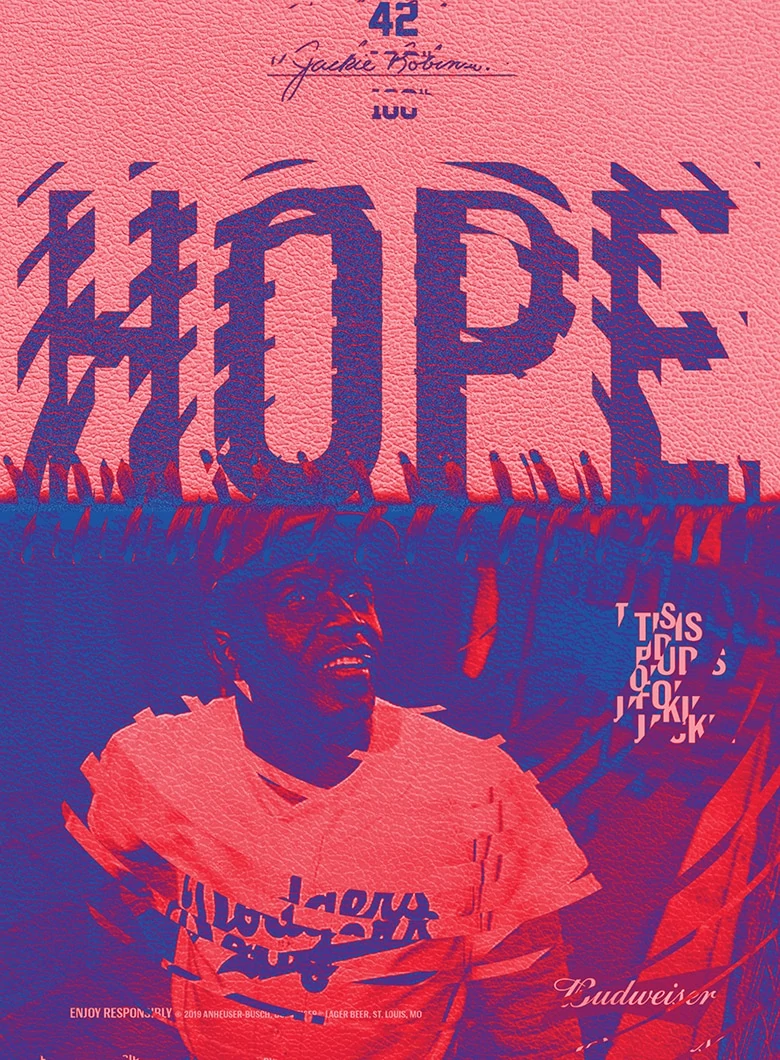

in a touching tribute to a singular athlete’s impact on his sport and community. But the very next week, Budweiser and Major League Baseball launched another socially minded ad, this time to commemorate the day that Jackie Robinson broke the sport’s colour barrier.

The simple ad featured a worker stitching together black-and-white baseballs before ending with the tagline “This Bud’s for you, Jackie.” Some writers and commentators felt that ad was all a bit cynical for both Budweiser and the MLB.

“There’s a thin line between honoring someone’s memory and using someone’s image and incredible strength to bolster your own corporate image decades after the fact,” tweeted baseball writer Evan Drellich.

In the end, the MLB deleted its tweet promoting the campaign.

There’s no shortcut to legitimacy

There’s a lesson here if your business is considering wearing its politics on its sleeve: if you fake it, you won’t make it past your audience’s BS detectors.

It can take years of steadily accumulating social capital for a brand to be able to use that capital meaningfully in marketing efforts—being known as a socially minded brand isn’t something that can just be bought in an ad campaign (we’re looking at you, Pepsi); it’s something that has to emerge organically from the brand’s history, its people and its actions.

Budweiser’s immigration ad worked because that was the story of its founding, while its Jackie Robinson ad came across as tacky because Budweiser didn’t (to our knowledge, at least) play a role in ending segregation in baseball. And while Anheuser-Busch has donated to the building of a Jackie Robinson museum, that kind of philanthropy isn’t baked into their brand DNA.

For Nike, identifying issues that resonate with young athletes and sneakerheads has been a major theme in their advertising for decades.

In 1995, for example, Nike produced both an ad featuring Ric Munoz, an openly gay, HIV-positive distance runner, and the famous “If you let me play” spot that encouraged parents to sign their daughters up for sports. Accordingly, aligning themselves with the Colin Kaepernicks and Serena Williamses of the world fits in with Nike’s well-established identity and doesn’t come across as opportunistic.

So, should you or shouldn’t you?

All of this shouldn’t dissuade you from incorporating issues you’re passionate about into your business.

But remember that advertising is just one of many ways to do so. If it’s your first foray into publicly supporting a social issue, consider starting small: quietly volunteering time and resources to help an organization in your community, for example, may not have the impact of a viral Superbowl ad, but it also won’t lead to thousands of people on Twitter dragging your brand through the mud.

Ultimately, it could be your first step on a journey to build a stronger company culture and a brand identity that you can feel truly good about, day in, day out.